Month: July 2020

Covid Time

So the question of the day is why does everything seem so much harder during the covid pandemic. Take today, for example. Now today was not all that typical since I actually ventured out of our apartment for a change. A typical day for me would mean an early morning walk with Embry to avoid the 95 degree afternoon heat, an hour or so of Dump Trump television (I am limited by Embry to no more than an hour a day of watching MSNBC.) and then working in my office on board stuff, blogging, or cartooning, followed by a happy hour starting at two and ending at six (slight exaggeration), followed by a Blue Apron dinner (prepared by me), PBS news (“balanced, trusted,” a tad boring) and maybe a series like “The Wire” or “A French Village.” There always seems to be at least one Zoom meeting thrown into the day somewhere. So that is basically it. Pretty routine, pretty boring, and for an extrovert like me, somewhat depressing.

But not today. Today was a very big deal because I had an appointment at Kaiser, our health care provider, to pick up rechargable batteries for my hearing aids. But I am getting ahead of myself. The day actually started at six this morning when Embry woke me up and said, “Go for it, get on your computer right now so we can reserve a swimming time five days from now!” I jumped out of bed and charged into my office to log on to my computer while Embry logged onto hers so we could make simultaneous reservations for two slots for lap swimming at the apartment house where we now live, the Kennedy-Warren. “Quick,” she shouted, “there is only one time slot left.”

I was nervous and still groggy from being waked up so abruptly. I was nervous because getting a reservation during Covid-time for the pool is close to impossible. We have been living at the Kennedy-Warren for almost five years during which time I have swum my 30 laps probably 400 times. I have never had to wait for one of the three lanes to open up and most of the time have had the pool to myself. Not now. During Covid-time it seems that everyone in the building (435 units) now wants to swim. You can reserve a spot up to five days in advance except there are never any slots available. I have complained to management that something does not make sense since I never had to wait for a lane before and could swim any time I wanted. Just to prove my point two days ago I set the alarm to wake up at midnight, so at 12:01 AM I could be the first to reserve a spot on the fifth day that would open up at that very minute. Admittedly, I was late. I did not get online until 12:15 AM. All spots were already reserved! Impossible I concluded. Thirty people at the K-W staying up late every night just to reserve a swimming spot as the clock struck twelve midnight. No way.

But today at six in the morning Embry had found an open slot for two swimmers at 2:00 PM on day five. With nervous fingers, I sat at my computer typing in my password. Denied once, denied a second time. Okay, I admit I was a bit nervous. And then a third time. A message came on saying that because of three wrong passwords, I would have to change my password. “Hurry up,” Embry shouted from the other room, “Time is running out. Someone else will beat you to it.”

I quickly came up with another password, typed it in again, only to be informed that the two passwords did not match. Tried it once more. Same result. By this time my fingers were really quivering and my heart beating madly. I tried really carefully and slowly the third time and was sure I typed in the same password each time when the message came on, “You have exceeded the required attempts to reset your password and are hereby denied access to this website.”

So that is how this Covid-time day started.

But the big outing was still on the agenda—getting on the Metro and going to the office of Kaiser Permanente adjacent to Union Station. All I wanted to do was purchase two hearing aid rechargeable Oticon batteries, which it turns out is not possible to do over the internet or in a drug store. But still in Covid-time this was a big deal and an excuse to get out of the apartment and to ride the Metro. In fact during the past four months that we have been under one form or another of covid-19 house arrest, I have not even been on the Metro.

I walked down to the Metro station after Embry and I finished our morning walk in the National Zoo (which reopened last week) and was astonished that at 9:15 I was the only person on the platform. And this was still rush hour! It took almost fifteen minutes for a train to arrive; and when it did there was virtually no one on the train. I got in the third car where there was only one other passenger. I felt completely safe since both of us were wearing masks but still amazed that so few people were using Metro. I did not see more than one or two people riding in the first two cars. Ghost town. Where was everyone?

The situation became even more bizarre when we roared into the Union Station stop to see another empty platform and only a handful of people getting off the train. The situation inside the usually packed Union Station was no different. I counted maybe a dozen people in the long corridor connecting all the gates. On a normal day at this time there would be a thousand people or more. I had planned to have a cup of coffee at my favorite pastry shop, but it was closed. In fact every food establishment in the vast station was closed except McDonalds, which, of course, I would not consider patronizing for a single moment under any circumstances.

So off to Kaiser, about a 15-minute walk through the vacant station, and then through a long, empty corridor connecting to the office building where Kaiser is located. There a nurse stood at the door, fully masked and wearing what looked like a hazmat suit.

“Do you have covid-19?”she asked.

“Nope.”

“Are you seeing a doctor because you think you might have it?”

“Nope.”

“Do you have a cough or sore throat?”

“Nope.”

“Can’t smell anything?”

“Nope.”

“Funny feeling in your toes or fingers?”

“Nope.”

She then took my temperature and said it was ok to enter the building. I thanked her but softly complained that all I wanted to do was buy a couple of hearing aid batteries.

When I arrived at the empty audiologist waiting room, I checked in with the receptionist to let her know I was here to pick up my two rechargeable batteries. After checking me in, she informed me that the audiology technician was not in and would not be in until the afternoon.

“Look,” I said, “She told me to come by and pick up the batteries. She said all I needed to do was to show up. For some reason Kaiser is not able to mail them to me. All I want to do is buy a couple of batteries. Isn’t there someone at Kaiser who can sell me two rechargeable hearing aid batteries?”

“No,” she replied firmly. “You will have to wait until two this afternoon, which is actually the time for your appointment anyway.”

When I protested that I was never given a time for an appointment and that it made no sense to have to wait four hours simply to purchase two hearing aid batteries, she excused herself and returned after talking to the audiologist and said that if I came back around eleven-fifteen—only an hour and a half later, the technician might be back, and I could buy the batteries.

Dejected, I retraced my steps back to the food station area of Union Station, muttering under my breath that this is ridiculous. Since I had not eaten breakfast, I figured this would be a good way to pass the time. Then I realized that all the food shops were closed except for McDonald’s. Me, eat at McDonalds? Well, given the alternative of not having any breakfast, it did not seem like such a bad idea. Actually, the Egg McMuffins are not all that bad, and there was no line. I got my Egg McMuffin and decaf coffee almost immediately, perhaps the fastest time ever.

So where to eat it? I looked around. The tables at McDonalds were stacked up and cordoned off with a sign saying something like “no eating allowed.” Just behind me, however, was one of at least a dozen enormous empty waiting rooms for train arrivals and departures. There were several hundred seats and only two people seated, both wearing masks and at least a hundred feet from me. I sat down and took a big bite out of the Egg McMuffin, an action which is impossible wearing a mask. So naturally I had taken off my mask off. Just before the second bite, I felt a tap on the shoulder and a person wearing a Union Station uniform reminding me, “masks required, masks at all times. No exceptions.”

“Oh, I understand that, but how can I eat with a mask on?”

She replied, “You can eat outside the station.”

The walk from where I was to the entrance to Union Station was at least 10 minutes. The place is enormous. A suggestion dead on arrival.

She then departed and I sat back down in my seat, ready for the second bite. The first bite of the McMuffin tasted so good. Her parting words were, “Well, you better be careful not to let a cop catch you.”

I shrugged my shoulders and took the second bite, then looked up and saw two huge, burly, masked men in police uniforms approaching me. I knew I was in trouble. I had been forewarned. All I could think of was whether they would they handcuff me. Would they put me in a paddy wagon? How much jail time would I have to serve? I was caught red handed with no excuses. I would go down as yet another casualty of covid-19. Guilty as charged.

Then miraculously just before they got to where I was seated, they made a sharp right turn and got in the short line at McDonalds, ordered what looked like a couple of Egg McMuffins and coffee, smiled at me, walked over to a row of empty seats, took off their masks, and ate their food and drank their coffee.

The morning ended with my returning to Kaiser, answering the same questions about whether I have covid-19, having my temperature taken again, and finding that the technician had returned. I bought the rechargeable batteries and returned home on yet another almost completely empty train. Welcome to Covid-time! Call the day a success.

But as I tend to complain about the new normal, at the same time I realize just how fortunate I am. Embry and I do not know anyone who has died from this dread disease or has been hospitalized. We do not have to worry about losing our jobs because we don’t have jobs. Our children and grandchildren are weathering the storm pretty well. We have stuff to keep us busy and have been able to travel to see family. We were even able to do a week of cruising on the Chesapeake on our sailboat. We have no right to complain. We are the lucky ones.

I think of the first responders, the medical personnel, and the essential workers who are on the front lines risking their lives every day. I think about those who have lost their jobs or are furloughed. I think about people who do not have the ability to social distance and live in crowded apartments. I thinks of all the students of all ages having to adjust to “virtual learning.” I think about people living from paycheck to paycheck and fearful of missing rent or mortgage payments. I think of old folks like me but who are not in good health and are confined to nursing homes or assisted living. I think of the 150,000 people in our country who have died and their families and the more than four million who have been infected.

While the new normal, Covid-time, is an inconvenience and annoyance to people like me, it is life and death to others. If anything good comes out of this horrid pandemic, it will be that we develop a sensitivity to those less fortunate, do something to level the playing field, and become a kinder and gentler nation and a better world.

Faux News Is Back: War Threatened With the UK

The Fox News Interview

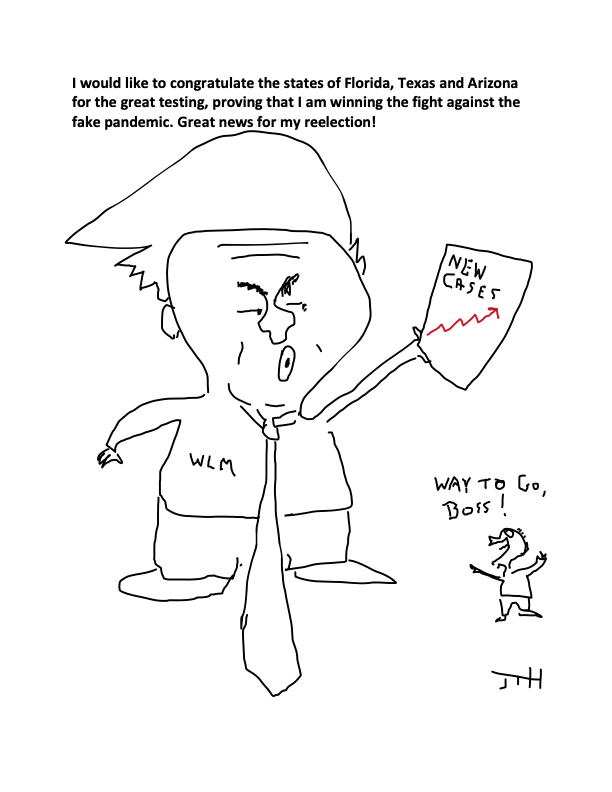

Trump Hails Cornonavirus Progress in Southern States

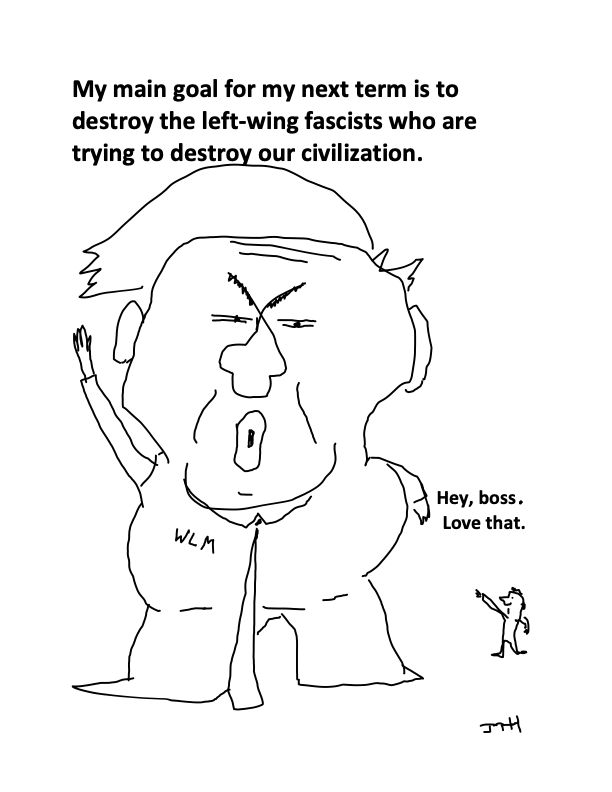

Trump’s Campaign Shifts Gears

Russian Bounties to Afghans To Kill Americans Is Another Fake News Lie