June 3

Chengdu

So here is the story of a 48-hour period of time, which in some respects is a poster-child for the entire Chinese leg. The day began at 4:00 am at our high end Hilton Hotel in X’ian so we would have time to pack and meet our guide at 4:30 am to take us to the train station for a 6:00 am train boarding to the village of Chengdu.

While the village was on our carefully prepared itinerary by Asia Transpacific, we knew very little about it except that it was on the way to Chongqing where we would board a ship to take us down the Yangtze, was near another small village (Leshan) where the world’s largest Buddha could be found and contained a large Panda Park with over 100 Pandas. Sounded like a nice place to stop before reaching the mighty Yangtze for our three-day river cruise.

Always punctual, our friendly guide met us and got us to the train station in plenty of time. This station was one of the older stations and not designed for bullet trains. Since there was no elevator or escalator, Embry and I had to haul our 50 pound suitcases down at least a hundred , very steep steps and then back up another hundred to get to Platform 2. After struggling for 15 or 20 steps and creating a bit of a roadblock for the hundreds of passengers racing for the train (which paused for only a few minutes in X’ian), a friendly hand appeared, lifted the bag from me and kindly left it at the bottom of the stairs. I wanted to thank him and shake his hand, but he was gone. Embry had similar luck. The same thing happened going up the stairs to Platform 2. This unsolicited, merciful aid has occurred every single time—both up and down stairs—when we have been confronted with this challenge. Would this have happened in the US?

So we made it to Platform 2 and there was our train, on time to the minute and pausing for desperate passengers to board. The train must have had at least 20 cars and we were assigned to “carriage 8,” probably somewhere in the middle. So that was where we bolted with luggage in tow, miraculously found the carriage where it should have been, and dragged ourselves and suitcases (again, with help from a lady conductor) up the steps into the carriage. Less than a minute later—on time to the second—the train pulled out.

Now there are a lot of things that our travel agents have done right in setting up this trip—terrific boutique hotels, excellent guides and tours, fine dining experiences, occasional evening entertainment with local dancing and singing—but nothing ranks higher on my list that buying four tickets for us for a “soft sleeper” compartment. That meant we had the entire sleeper compartment to ourselves on a sold out train. There is no way we could have gotten ourselves and our baggage into the tiny compartment if we were sharing it with two other people. Some of the compartments even had six berths instead of our four! Way to go, Asia Transpacific!

Even though it was only 6:00 am, I collapsed, went sound to sleep and when I woke up around nine found myself in a different world. The scenery was now lush and green with no hint of the mainly semiarid landscapes we had been witnessing for the last several weeks, starting in Mongolia. We were in fact in what resembled a rain forest—and it was appropriately raining outside—with towering peaks above us on both sides and no sign of any roads or houses, only occasional mountain goats perched precariously on steep cliffs. This breathtaking scenery would be with us for the next 12 hours with no letup. The only changes would be that a tiny village would appear every now and then, many with no apparent roads to connect them to the rest of the world. Valleys would also emerge below occasionally with cultivated fields—rice fields, which we were seeing for the first time—and larger village clusters. After a few hours of chugging up hill at 40 or 50 miles per hour, we started to head down the mountain, picking up speed and following numerous rivers and streams, some with many class 2 and 3 rapids. Occasionally we would see flimsy foot bridges and when there was a calm spot in the river, a small barge serving as a ferry. And toward the end of the journey—which lasted for some 17 hours—larger towns appeared, a few with large factories. We learned after arriving Chengdu that we had crossed the second tallest mountain range in China, separating north China from south China, with peaks in excess of 4,000 meters or over 12,000 feet.

The only frustrating thing about the journey was that about half of it was through tunnels. Just as you were marveling over the most beautiful landscape you had ever seen, bingo, all black, and you were in a tunnel for a good five minutes before you emerged, and it all repeated itself minutes later. Perhaps the biggest surprise was lunch in the dining carriage, which turned out to be spectacular though we had no idea what we had ordered since nothing was in English. And the most disgusting? The rest rooms, which were filthy, in stark contrast to the spotless rest rooms on the bullet trains.

Since it got dark at 8:30 and we did not arrive in Chengdu until almost 11:00 pm, we missed a lot of the dramatic scenery for the last one hundred miles or so. As we approached the village, I was aware that there were a lot of lights outside and that the village was probably not really all that small. When we rolled into the station and dragged ourselves and baggage off the train and then, with good Samaritan help, got the bags down and then up steep staircases, we found ourselves in what could easily have been Penn Station. It was almost midnight, and the huge station was jammed packed. A bit disoriented, we stumbled to the exit hoping to find a smiling guide holding up a “Howell” sign, and there she was—a petite, 20-something with a broad grin. How could anyone do a trip like this without a guide?

As we crossed the huge plaza, buzzing with people and with many people sleeping in sleeping bags along the side (Aha—so there is homelessness in China after all, I said to myself, only to discover later they were college students with a very early train to catch the next day), I asked the obvious question as to the size of this “town.”

“Carol” replied, “Officially only 16 million. Unofficially probably a lot more, maybe 20 million. We are a middle sized city in China.”

That moment you could say was my Epiphany. It was finally dawning on me just how big this country is.

By now we were pretty familiar with the protocol. The guide charges ahead. We follow as best as we can, but I usually fall back so far I fear I will get lost and will never be seen again. She momentarily stops—this time on a street more jammed with honking cars than Times Square—and a car and driver mysteriously appear out of nowhere. The driver takes the bags, throws them in the trunk , we hop in, and off we charge to the hotel, honking madly, swerving to miss jay walking pedestrians, swerving again to miss pedestrians on cross walks but, God forbid, never stopping for them, which as far as I can tell is some kind of unwritten rule, and dodging in front of a smaller car when you need to change lanes. Then there are the countless bicycles and electric motor bikes heading at us in our lane, going in the wrong direction and dipping in the tiny spaces between two cars stuck in traffic. Somehow the driver manages to miss them too and the hundreds of people legally crossing on a red light for us when we make a frantic right-on-red and plow through them as they scamper to give us room. You would think I would be getting used to this by now, but frankly it is having the opposite effect; and when we get back to the US, I am certain I will have to check myself in to Kaiser with Level I Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome.

But I have got to say, the Chinese drivers have to be the best in the world. Over three weeks in this country, observing more near head-on collisions and pedestrian wipe outs than I can count and not one sighting of an accident of any type.

We arrived at our hotel after midnight. A quaint, 35-room traditional Chinese hotel, it is nestled in one of the historic, protected areas, which is quiet and peaceful with narrow streets, which during the day fill up with vendors. There is a large, active Buddhist temple and monastery around the corner. We were completely wiped out and collapsed and fell into bed at close to one in the morning.

But we were in a new city. When you get to a new city, your guides are rested and ready. They are bursting with enthusiasm and energy, and they want you to see everything. That is their job. Their enthusiasm is contagious, and you want to see it all too.

So before we headed to our room, Carol suggested we start early in the morning. She would pick us up at eight and we would head out for the two hour plus drive to Leshan were we would see the world’s biggest sitting Buddha, followed by a nice lunch and then a full tour of Chengdu and then dinner and authentic entertainment at the world famous Chengdu Opera. All on the itinerary, all paid for in advance. Sound like a plan?

While she was going over all this at one in the morning, it already was the next day, and I was wondering how I would get through the night, let alone tomorrow. It is times like these when we had young guides, that Embry would pull out her grandmother routine. It usually went something like this:

Embry: ”Is your grandmother still alive?”

Guide: “Yes.”

Embry: “How old is she?”

Guide: “Seventy.”

Embry: “That is my age and my husband is almost four years older. Do you think your grandmother could do all this?”

Argument over. Worked every time. We settled for departing at 9:30, a half day visit to see the great Buddha and no afternoon activities, no dinner and entertainment to be discussed later.

It would have been nice if it had turned out this way. But actually it was our fault that it didn’t.

First the Buddha. My idea of what the day would be like was that we would take an ancient, two lane road through villages arriving at an isolated and holy spot in the middle of nowhere. As we inched our way in heavy traffic out of Chengdu, we made it onto an eight lane, super highway that was like the New Jersey Turnpike except more crowded. For almost the entire two hours we were on that road (which eventually did narrow to four lanes), passing through rice fields and tiny, prosperous looking villages. As we got closer to the tiny village of Leshan, first a 30 –story, modern apartment appeared, then another and soon the landscape was covered with towering high rises and tower cranes.

“What is all this about?” I asked Carol, who promptly responded that we were now in Leshan, a small city of three plus million people official, maybe four or five unofficial. So much for the tiny village idea until I realized that in modern day China, Leshan actually is a small village.

The Buddha was great. It was something like 275 meters high, carved out of a mountain side over a thousand years ago. We boarded a boat carrying about 50 passengers, all Chinese except for us, and viewed this ancient wonder from the water. Peter, our son-in-law who is himself a Buddhist, emailed us that this famous Buddha is not only the world’s largest, it is the largest pre modern sculpture of any kind in the world.

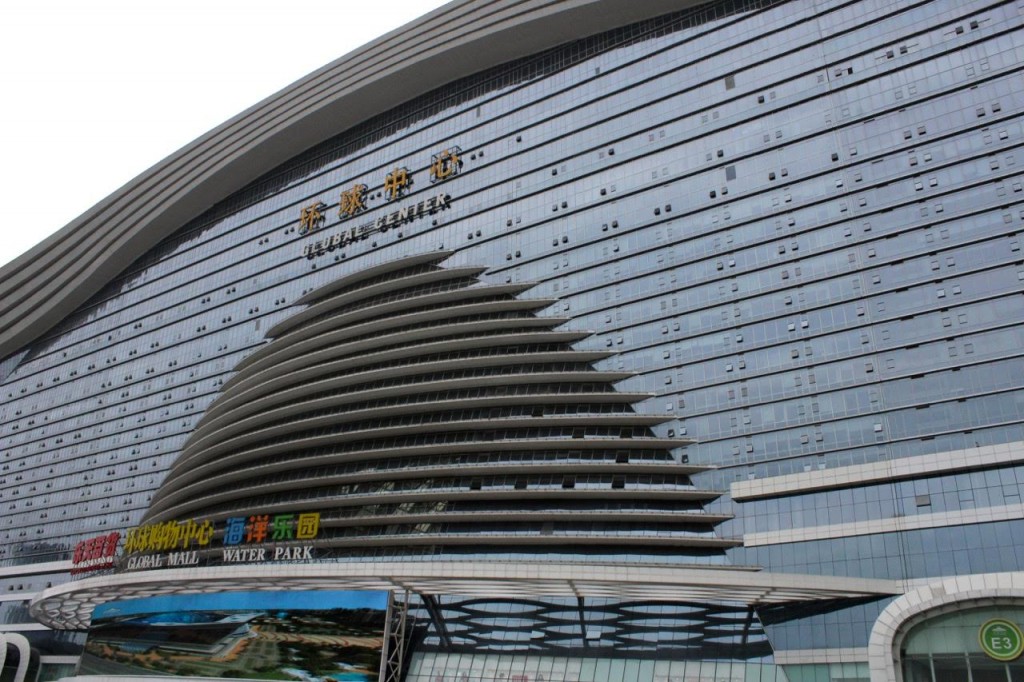

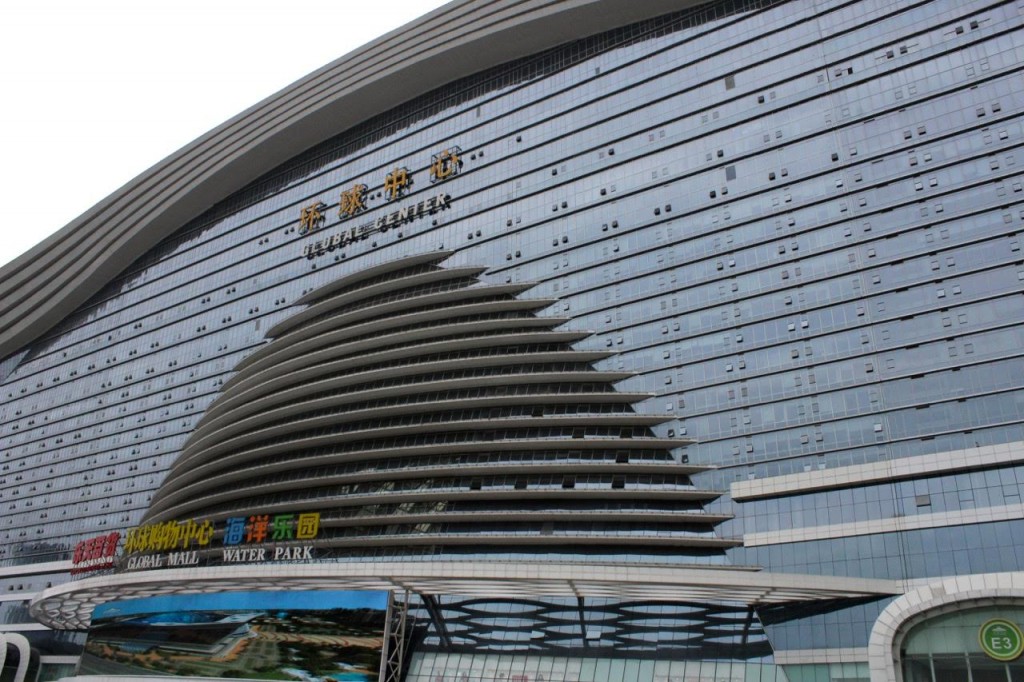

We then had lunch at a nice riverside restaurant before heading back. Our strategic error with regard to scheduling was that on the way to Leshan we had passed by a huge structure that looked like FedEx Field (100,000 seat football stadium) cubed. When we asked Carol what it was, she said it was “Global Center,” the world’s largest building, which opened about a year ago and was primarily a shopping mall with a hotel and a water park. We had to see it. Though it was not on the itinerary, we made the side trip, which was worth it. We counted the stories: 27. We estimated the footprint: at least twelve football fields. The size and scope of the mall inside is indescribable—every multinational chain store in the world represented with huge stores, a water park similar in size and scale to something you would find at Six Flags or Disney World, regulation size ice hockey rink, health clubs, restaurants, an Imax movie complex of something like 50 theaters, escalators going up eight or nine levels, a floor made from precious jade that resulted in the leveling of an entire mountain in Burma. The list could go on. And at 5:00 pm on a week day, plenty of people were walking around, ogling just like we were. Marx and Mao, is this what you had in mind?

So that is why we did not get back to our hotel until around six, just in time to shower and change clothes for the Chengdu Opera, which did not disappoint. We returned to our hotel around ten.

As we were getting out of the car to head for the hotel, Carol enthusiastically reviewed the next day’s agenda. Start at eight, morning spent visiting the Pandas, special “hot pot” lunch, tour of the city….

Time for Embry’s grandmother speech again. And if you are counting, at 10:O0 pm, we were only on hour 42. The 48-hour mark would not arrive until 4:00 am. Not a typical two day period but one close enough to give you the flavor of our Chinese experience.